GRIMSBY FISH DOCKS: AN ASSESSMENT OF CHARACTER AND SIGNIFICANCE

By Matthew Whitfield Architectural Investigation Division (North)

April 2009

Summary

- Grimsby became the largest fishing port in the world in the late-19th and 20th centuries, based on its provision of specialist fish docks, marketing facilities, fish processing infrastructure and rapid transport systems

- The landscape of docks, quays, transport systems and specialised building types within the Fish Dock ‘peninsula’ and adjacent land forms the most important representation of the industrial-scale fishing trade in England. This landscape and its constituent buildings survives with a high degree of integrity and forms a unique environment of great historic interest

- The Fish Dock peninsula has a strongly distinctive character, unique in England, conferred by the association of features connected with the fishing trade, including not only the immediately striking fish smokehouses but also shops, warehouses, commercial and social facilities, marketing spaces and transport systems

- The Fish Dock peninsula and adjacent land displays the largest concentration of fish smokehouses in the country: six smokehouses are listed at Grade II, and twelve other survivals were identified as significant in 2002

- The Grade II* listed Grimsby Ice Factory is a nationally significant building illustrating the industrialisation of the fishing trade in the early 20th century

- Consideration should be given to providing the area with statutory protection to preserve and enhance its unique and nationally significant character

- Introduction

Reasons for this report

This report has been commissioned by English Heritage’s Planning and Development (North) department, to inform their discussions with North East Lincolnshire Council regarding the future development of Grimsby’s fish dock area. Its primary purpose is to provide an overview of the historic significance of the area, in the context of the development of Grimsby as a port of the railway age and as the centre, within living memory, of the largest fishing industry in the world, and to describe the special character of the area.

Area Boundaries

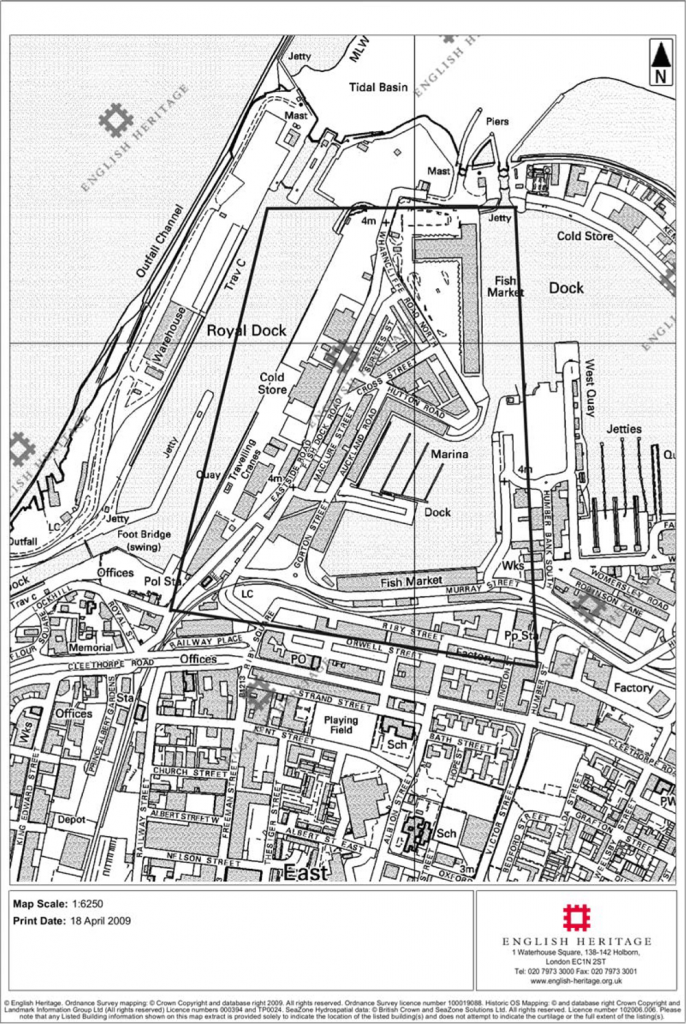

The area under consideration in this report is centred primarily on the ‘peninsula’ of land in Grimsby situated between the fish docks to the east and Royal Dock to the west, and bounded to the north by Wharncliffe Road North and the modern Fish Market on the quayside of Fish Dock NumberThe area also extends southwards to include the Dock Offices and the length of Riby Street. See Appendix 1 for a map.

Methodology and Sources

The research for this report has been very largely desk-based, relying on a range of secondary literature about the history of Grimsby, and a series of internal and commissioned English Heritage reports that relate to the historic significance of various aspects of the dock area. Use has also been made of modern and historic maps, as well as copies of Goad insurance plans for Grimsby docks sourced from the North East Lincolnshire Archives. The report has been produced within a two-week period in order to respond rapidly to the commission, and represents as full an analysis as has been possible using the available sources in the available time. It has been researched and written by Matthew Whitfield, with additional advice from Adam Menuge and Colum Giles. Lucy Jessop provided help with the illustrations.

Historical significance

The development of Grimsby’s dock system

Fishing made Grimsby, as even the briefest analysis of the town’s economy over the last 160 years demonstrates. The town has a history that stretches far beyond the mid-19th century, however, and it is instructive to appreciate that the 19th and 20th century fishing industry that provided the town with a booming livelihood and a rich legacy of historic buildings is, in fact, only the most recent and visible expression of a flair for trade that was intrinsic to Grimsby’s naturally advantageous position at the very mouth of the Humber estuary. Pevsner et al note, for instance, that the town had well-developed and sophisticated patterns of trade across northern Europe and Scandinavia in the Middle Ages, with the 13th century in particular giving rise to a flourishing fishing trade, as reflected in the quality of the earliest parts of the parish church of St James (1). Relative decline in the 16th and 17th centuries gave way to a new wave of speculation in the 18th, when Grimsby’s first dock, known as the Haven, was constructed from a natural inlet in 1798-1800, engineered by John Rennie.

The first dedicated fish dock at Grimsby – now incorporated into No. 1 Fish Dock – was constructed between 1855 and 1857, on land reclaimed from mudflats in the River Humber (2).This scheme, highly significant as it was for the future of the fishing industry in Grimsby, must be understood in the broader context of the development of the modern port from the mid-1840s onwards. The creation of a new dock estate, driven almost entirely by the new economic possibilities created by the railways, fully realised Grimsby’s potential advantages as a port and positioned the town as a key nodal point in a newly invigorated network of capital and communications that would bring it wealth and national recognition as never before.

The initial impetus for this phase in the port’s development flowed from a merger of two newly-formed companies – the Grimsby Dock Co. and the Great Grimsby & Sheffield Junction Railway Co. – in October 1845, when the five directors already common to both concerns decided to form an integrated business that could exploit Grimsby’s commercial potential in the new railway age. A new dock to replace the inconvenient and silted Haven was commissioned shortly afterwards in spring 1846, designed by James Rendel and engineered by Adam Smith of Brigg (3).

During construction, a series of railway building schemes and amalgamations set the scene for an accelerated economic boom for the port. The Great Grimsby & Sheffield Junction Railway Co. was merged into a larger, more powerful company, the Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway, and, during the course of 1848-49, Grimsby was linked in stages with Sheffield and the major rail networks of the midlands and the north. In the same year, 1848, the East Lincolnshire Railway began operating a south-bound service from the new Grimsby Town station to Louth – this line was leased to the Great Northern Railway as part of what would quickly become a direct route to London King’s Cross.

The new dock was completed in March 1852 (it was named the Royal Dock in 1854 following a visit from Queen Victoria), providing the basis for a massively expanded trade in a number of commodities across the North Sea and the Baltic, including cotton, salt, iron and agricultural machinery, but particularly coal and timber (4). The growth of the port’s business was rapid, so that by 1865 it had risen to the position of the fifth largest in the UK (5).

The fish trade in the northern portion of the North Sea was developing rapidly at precisely the same time as these developments in Grimsby’s port infrastructure. Although there was no direct intention on the part of the Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR) to encourage this specific trade from the outset of their dock developments, fishing smacks nevertheless began to exploit the facilities of the port in earnest, initially using both the new Royal Dock and the Haven. The advantages of Grimsby over Kingston-upon-Hull, its nearest rival in the fishing trade, were apparent – namely, the potential of a swifter land route down to the key market of London, avoiding the diversion around the Humber estuary, and a position much closer to the open sea, eliminating the wait for a favourable wind to take boats down the river from Hull. These were the factors that naturally attracted the smacks in the first instance, but investment was required if the long-term problems that the industry had faced in Hull – of overcrowding and competition for space from the general cargo trade – were to be avoided. Smacks may have used Grimsby, but in the early stages of this trade very few fishing concerns were prepared to use it as their official home port.

The first fish dock of 1857 was a straightforward response by the MS&LR to the pent-up market demand for Grimsby as a viable fish port, especially since the town’s connection to the rail network in 1848. The opening of the dedicated dock had an immediate and dramatic effect, doubling in just one year the weight of fish landed to 3,400 tons (6). A little over a decade later, in 1869, the amount of fish moving by rail from Grimsby had reached almost 20,000 tonnes, and the MS&LR began work on an extension of the original fish dock (7). Expansion towards the end of the 19th-century was even more rapid, with an additional fish dock opened to the south of the original facility in 1877, which itself was later extended to cope with the increased demands of steam-powered trawlers from the 1880s onwards (8).

In the first half of the 20th-century, the fishing trade was not as secure as it had been in the late 19th-century, with over-fishing affecting the reliability of stocks. Meanwhile, the ‘group’ reorganisation of the railways in 1923 led to the docks at Grimsby coming under the auspices of the London & North Eastern Railway (LNER), a body which appeared to lack the entrepreneurial dynamism of its 19th-century forbears the MS&LR and, from 1897, the Great Central Railway. A third fishing dock, which in essence represented a massive eastwards extension to Number 1 Fish Dock, was commissioned and built by the Corporation of Great Grimsby in 1933-34, to be subsequently let to the LNER on a 30-year lease. Although the impetus for growth was now emanating from the local council rather than the private business interests that had initiated Grimsby’s 19th century prosperity, the extension of port facilities for fishing remained a statement of belief in the enduring prosperity to be won from the fishing trade, with the potential for accommodating larger boats and creating more quayside buildings to support the industry.

A Railway Dock

Gordon Jackson has described the development of Grimsby’s port in the 1840s and 1850s as representing the ‘first truly modern dock in Britain” (9). This claim is based on the almost wholly novel and comprehensive application of communication and engineering technologies in the creation of the Royal Dock and its subsequent neighbours. This innovation was possible, of course, because the Lincolnshire landowners who decided to speculate on Grimsby’s economic potential by means of a merged dock and railway company were doing so at a time of enhanced technological possibility, but also because the chosen location, being hitherto undeveloped, offered a clean slate. In fact, the port depended for its success on the integration of docks with a rapid transport system.

Whereas older, well-established ports such as London, Liverpool and Hull had systems of docks that long pre-dated the railways, and which were physically very closely integrated with the city streets that surrounded them, Grimsby was a relatively small town offering fewer constraints on the introduction of railways into its docks. James Rendel’s design for the new dock at Grimsby was not only the best means of creating a reliable and large harbour – by annexing a large swathe of the foreshore behind a coffer dam – but by means of its shape and location it also created a situation in which the railway could penetrate deeply into the new facility, providing quayside services alongside the suitably long frontages of the dock. All of the construction and the operation of this integrated transport system took place well away from the historic core of the town, reducing both the capital costs and the day-to-day disruption that a fully functioning railway port would otherwise have brought. Aside from the Haven dock, Grimsby had none of the historic obstacles to such advanced development, and in its sequence of new docks the MS&LR was able to create a new dock estate that was ideally suited to railway transit from the outset.

The achievement of Grimsby in creating a port effectively from scratch that directly reflected the technological achievements of the mid 19th-century was virtually unique in Britain at the time. The only other port that was being developed in quite this way during the 1840s was Birkenhead, also designed by James Rendel, but through a series of engineering failures in the new docks and financial crises in the setting up of a rail link, this scheme faltered and in 1855 it was sold to the very body it was meant to compete with, the Corporation of Liverpool, to be integrated into the broader dock estate on the Mersey. Grimsby’s scheme, by contrast, was an unqualified success, and its achievement was to rival its nearest neighbour Hull in numerous trades by investment in the most up-to-date technology.

The modernity of Grimsby’s new dock venture was, in fact, the only substantial means by which it could have possibly achieved this success. As Jackson has demonstrated, setting up an almost entirely new port venture in order to compete with established centres of trade was a highly challenging business, as maritime commerce was deeply entrenched in customary patterns, with a profound aversion to change. Trading links followed the shipping companies, and these tended to be located in the historic ports, as did all of the services that accompanied the core activity, such as brokerage and insurance (10). The groups of merchants that financed and directed shipping would not yield lightly to competition from a new direction, and so to succeed, Grimsby had to prove that its claim to viability and utility had some firm basis. The crucial advantage that Grimsby enjoyed as a railway port was the sort of inland connectivity directly from the quayside that other ports took longer to develop, and it was this connectivity – to the coal producing and manufacturing areas of South Yorkshire, Lancashire and the Midlands, and to London via Louth and the Great Northern Railway – that enabled the port to compete and to succeed, at least in the medium term. This rapid and direct communication with the capital and the great cities of the north and the Midlands was of special benefit to the fish trade that came to dominate and characterise the town, as it was a particular advantage if perishable goods such as fish could be delivered to their destinations without delay, and with a certain degree of flexibility and responsiveness built in to the systems of delivery.

The Dock Tower and the hydraulic system

The modernity at the heart of Rendel’s plans for what became the Royal Dock was given its most acute built expression in the Dock Tower, built to designs by J.M. Wild in 1851-52. Standing at over 300 ft, the tower was central to the hydraulic system that powered the entirety of the new dock’s mechanical aspects, creating the required water pressure by sheer height alone. This system involved the use of pressured water to power not only the large lock gates required for the most up-to-date steamboats but also the heavy cranes that ran along rails at the quayside, able to handle much bulkier cargoes than had been possible using older technologies, and in rapid and flexible manner, too (11).

Rendel’s was the first application in Britain of a complete hydraulic system to a dock estate, as opposed to the piecemeal introduction of hydraulic machinery to existing installations and buildings. This fact alone marks out the significance of Rendel’s achievement at Grimsby, but the Dock Tower, which quickly became a noted landmark and seamark, is the lasting monument to this moment of technological and commercial ambition. In the vein of many 19th-century civil engineering schemes that attempted to echo the achievements of past societies, the building took as its stylistic inspiration the tower of the 14th-century Palazzo Pubblico in Siena, a centre for European trade in the Middle Ages. By means of its not inconsiderable symbolism as much as its practical applications, the Dock Tower has provided an imposing and distinctive backdrop to the everyday activities of the docks and their estate of working buildings for more than a century and a half.

The development of Grimsby town

By creating a modern railway port, competing for prominence with the top tier of British ports and instigating a streamlined fish-processing industry par excellence, 19th-century Grimsby rose quickly to national significance, but the birth of the town’s new docks also had a more local and regional impact. Grimsby was able to attract an entirely new population to its booming port, and rapidly, too – the 1851 census showed a doubling of the 1841 population to 8,860, even before work on the future Royal Dock had been completed. Such a steep increase was obviously caused principally by economic migration, originating mainly in the town’s rural Lincolnshire hinterland but also further afield. This population explosion played a large part in prompting the reshaping of the town during the latter half of the 19th-century and beyond. Its effects were experienced perhaps most keenly in the East Marsh district (6) immediately to the south and south-east of the docks, a largely residential, working-class area that was laid out on a grid-iron pattern either side of Freeman Street.

Character and Distinctiveness

Layout and scale

The layout of the entire dock area is constrained and influenced not so much by the available space and the requirements of buildings, but by the overwhelmingly dominant land-use requirements of transport, particularly the railway. The resulting pattern of streets represents an entirely logical arrangement of spaces between busy, working docks, and the accommodation of a railway system that was at the heart of Grimsby’s late 19th-century port.

At the centre of the dock area is a core block of streets that responds, in the most pragmatic way, to the space made available by successive waves of embanking the foreshore and the construction of wet docks. Within this man-made peninsula, the central core is made up of three streets – Fish Dock Road, Maclure Street and Auckland Street – running straight and parallel between the Royal Dock and the fish dock complex. Beyond this central core, to the north-east and south-west, there are several variations and disruptions to a straightforward grid iron pattern, most notably in the examples of Cross Street and Parker Street, laid out diagonally across the general street plan, and originally the route of railway branches providing direct access to the quaysides (see Appendix 3). The northernmost section of the built-up area broadens into a triangular plan and extends towards the principal fish market at the quayside of Fish Dock Number 1 – this is where the majority of the fish processing buildings are found. The entire area is defined and constrained on all sides by the water of the docks, of course, but also by the wide quaysides which provided the space required for loading, temporary storage and transport. This space is particularly large on the Royal Dock side of the area that is used today, as it was in the 19th century, for transit sheds, marshalling and loading, etc. The only significant difference is that rail traffic has been replaced with road haulage and the railway branch that once defined the edge of the built-up area is now replaced with Eastlake Road.

This is a built landscape that has been shaped, if not quite by laissez faire principles, then certainly by an overwhelming sense of economic logic. The rationale of the street plan can be plainly seen, but the available building plots were evidently subservient to the careful and spacious planning of the docks and the railway as an integrated system. There is a strong contrast between the built-up sections of the area and the open spaces reserved – both today and historically – for different forms of transport and logistics. Roads, including those that once carried railways as well, and open marshalling areas for cranes, sidings and transit sheds etc. are arranged in such a way as provide 7 the optimum space for their function. Within the blocks of buildings, meanwhile, there is scarcely any open space at all, with densely developed, continuous rows of buildings being the dominant form. The principal functions of the area, the storing and processing of fish, required little natural light, and so plots could be fully exploited and built-up. These buildings were arranged, therefore, to make the most efficient use of scarce land, whilst remaining as close to the quayside and rail-links as possible.

This principle can also be observed in the southern section of the report area around Riby Street, which represents a slightly later phase in the development of dock-related building. Here, we see how previously undeveloped and irregular parcels of land that lay between Number 2 Fish Dock, the Cleethorpes branch of the railway, Cleethorpes Road and the northern tip of the East Marsh residential district were filled up from the 1890s onwards to provide a much-needed expansion of the port’s industrial capacity. There is much less regularity in the layout of this section than on the main dock peninsula: the railway is even more obviously the dominant influence and buildings have been developed in a piecemeal fashion along this transport corridor.

The built-up dock area is of a broadly consistent scale, typically of two to three storey buildings with very few exceptions. Within this broad pattern, however, lies a huge amount of localised variety, with very few consistent ranges of two or three storey buildings aligned together. This is, of course, a reflection of the considerable variety of building types and the multiple functions of the area in relation to all aspects of the fish trade, and the manner in which the available building land was developed by a number of separate interests. Appendix 4 shows something of the generally low-rise but complex arrangement of buildings within a highly proscribed and functional landscape. There are certain key examples of this pattern of building, such as the tightly-packed block between Fish Dock Road and Surtees Street where the notable variety of height, storey size, massing and elevational style all reflect the dynamic development of this area for different functions and at different periods (see Appendix 5).

The typical site plan of small, individual buildings is generally deep and with a narrow frontage, but in a number of cases multiples of these plots have been developed from scratch or redeveloped over time to create much larger units. Within this general site plan, or multiples of it, there is considerable variety in the forms of each of the buildings, each one revealing something of its original use but overall reflecting the diversity and dynamism of commercial activity within the dock area.

Building types and the functions of the dock area

As the land surrounding the Royal Dock and the sequence of Fish Docks in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was developed, a readily identifiable pattern of building took place that reflected both the practical requirements of the docks and the multiple opportunities for innovation and profit that emerged from Grimsby’s industrialised port 8 system. The majority of the buildings in the area examined by this report were closely or exclusively associated with the fish industry, linked in some way to the multifarious aspects of this trade, from landing and marketing to processing and despatch. There were indeed a number of other trades associated with the buildings along Grimsby’s quaysides, but fishing was undoubtedly dominant, and it is the buildings associated with the trade in general, and certain of the building types in particular, that contribute most keenly to the area’s special character.

The date range of the buildings in this area runs from the creation of the dock complex in the 1850s to contemporary structures from the last 20 years, but within this long period of development, the majority of buildings are largely of the period from 1860 to 1910, when the most dramatic growth of the fishing industry took place.

Perhaps the most frequently occurring building type in all sections of the area under consideration are the various stores and warehouses that were used to house numerous goods – primarily fish, in both its fresh and processed state, of course, but also the infrastructure that supported the landing and treatment of the product. These included cold stores, for the longer-term storage of fresh fish before transit, and other forms of fish warehouse specially adapted to a variety of stages in the handling and processing of fish. There were also numerous items on which the fish trade relied that also required storage nearby, not least of all the many boxes and huge quantities of ice and salt that were prerequisites for handling fish after its landing in the market, and for onward railway transport across the country. Much of the remaining warehouse space was taken up with items that were associated with boats and the landing of fish, with numerous units dedicated to the storage of coal for steamships, castings and nets, sails, rope and other forms of rigging.

Alongside this warehousing space lay a variety of supporting trades that were essential to running a fishing fleet and the efficient operation of the docks in general. Although not always specific to either Grimsby or the fishing industry, facilities such as smithies, garages, engineers, joiners, chandlers, shipwrights, rigging/sail manufacturers and saw mills were all essential parts of the dockside community of businesses, and were integrated tightly into the streetscape of the working port.

The operation of the whole range of quayside businesses, both large and small, was obviously dependent on more than its workshop and storage space, and most of the buildings in the area had at least some portion of their plan given over to offices for administrative purposes. Some of the larger concerns had identifiably separate office buildings, but mostly there were ranges that combined a number of different functions, with clerical and managerial work in close physical proximity to a variety of industrial activities.

One of the most notable forms of this type of building with a combined function were the shop and warehouse ranges, typically fronting onto the principal streets within the 9 area, and supplying a variety of goods on a business-to-business basis and to individual fishermen and other workers. Two examples of this building type – Tom Tailors fisherman’s outfitters and a building that formerly housed the Cosalt butchers – have been listed at Grade II, reflecting the importance of these structures to a built environment that was densely layered with a series of functional spaces related to the storage and selling of numerous goods.

As a busy working environment which operated at some remove from the historic core of Grimsby, the docks were also supported by a range of tertiary services that were essential to the convenience of the numerous businesses that operated in the area, and to the many individuals that spent their long working days there. In addition to the various retail outlets supplying the day-to-day needs of both trade and personal customers, there were numerous facilities that underpinned the commercial and social infrastructure of the docks, such as a Post Office, a number of banks and even a clinic.

One of the core functions of the dock area was, of course, its provision of fish markets. The close physical connection between quayside, marketplace, processing facilities and the rail-link to London and the major markets of England was the principal strength of Grimsby’s port, providing an economic advantage by means of the smooth and extremely efficient operation of the commercial spaces within the dock area. The fish markets were situated on pontoons floating on the eastern edge of the fish dock peninsula, occupying a space at once transitional and transactional between the water and the land. Here fish could be freely traded, sorted, and either taken away fresh to where it was required or moved immediately onshore for curing, smoking and other forms of processing. The earliest structures that served this purpose during the height of Grimsby’s fishing industry have been swept away, to be replaced by a variety of buildings from the second half of the 20th-century – the largest of these, on the quayside of Fish Dock Number 1, was built in 1996. Despite these losses there is a continuity not only of function, but also of scale and setting, with single-storey buildings lining the edge of the quayside.

Buildings directly associated with various aspects of fish processing have, by means of their highly specialised use, distinctive form and massing and historic significance, provided the area of Grimsby’s fish docks with the majority of its listed buildings to date. Although curers, ice factories, smokehouses, etc, did not represent the majority of the buildings within the dock area, they were the most singular in their conception and operation, and were of course unique to areas that had a significant fish industry. As Grimsby was, by most measures, the largest fishing port in the world by the end of the 19th-century, the continuing presence of these buildings – both listed and unlisted – represents an invaluable body of built evidence about the way in which the fish processing industries were operating in the town at the height of its prosperity.

Listed buildings

There are nine listed buildings in the area covered by this report. This selection consists of one Grade II* building and eight Grade II buildings. Beyond the direct consideration of this report, but still highly significant in providing a landmark and a backdrop to all of the other listed and non-listed buildings in the area, is the Grade I listed Dock Tower, located between the lock gates of the Royal Dock to the north-west of the report area. These buildings (aside from the Dock Tower) all range in date from the late 19th-century to the early 20th, from the 20-30 year period when the economic and physical development of the docks was most rapid.

The majority of the buildings that have already been listed are fish-processing facilities, concerned with the curing and smoking of fish. These were either purpose-built for their task or adapted from previous fish-related buildings along the quayside, but they all contribute significantly to the special character of an area that was highly specialised in its commercial and industrial activities. The following fish-processing buildings are listed Grade II:

- MTL Fisheries fish processing and smoking factory, Fish Dock Road (east side)

- Quality Fish Company fish smoking factory, Henderson Street

- Peterson’s Fish Processing and Smoking Factory, Henderson Street

- Abernethie Ltd, Fish Curers, Sidebottom Street

- Keith Graham Ltd., Fish processing and smoking factory, Sidebottom Street

- Russell Fish processing and smoking factory, Riby Street

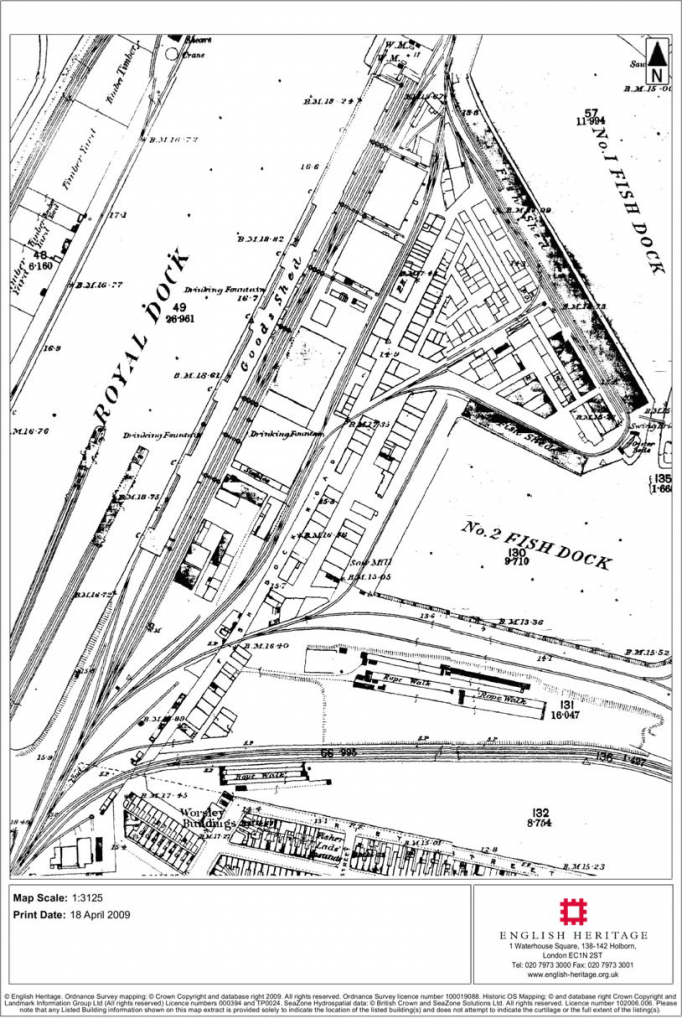

These buildings, along with many other fish-processing buildings, are (with one exception) concentrated in one particular area, in a roughly triangular-shaped area bounded by Fish Dock Street, Henderson Street, Cross Street and Hutton Road. The single exception is in Riby Street, to the south of Number 2 Fish Dock, and is representative of a separate phase of development in the later 19th and early 20th centuries when a number of smokehouses were developed along previously-undeveloped land squeezed between the Cleethorpes branch of the railway and the working-class housing of the East Marsh district (see Appendix 2 for an 1890 map showing the Riby Street area before this development, contrasted with the peninsula). In a survey in 2002, twelve other fish processing facilities that included smokehouses were identified within the report area (12).

The two other buildings in the area listed at Grade II represent another distinctive building type – the combined warehouse and shop – that was typical of the major thoroughfares in the area, but particularly Fish Dock Street. These buildings reflect the day-to-day commercial life of the working port and the multiplicity of uses of many buildings on the docks, but also the not-inconsiderable architectural effort embodied in the decorative aspects of elevations that fronted major streets and junctions. These were the kind of buildings that were designed with more than a purely functional dock streetscape in mind, but also the commercial concerns of architectural display.

- Former butcher shop and warehousing, part of Cosalt estate of buildings, at corner of Fish Dock Road, Hutton Street and Cross Street (See Appendix 5)

- Tom Tailors Shop and warehouse, Fish Dock Road (east side)

The former Grimsby Ice Factory on Gorton Street, listed at Grade II*, is of such high importance because it is the earliest surviving example of its kind in England, built in phases between 1901-08, and thought to be the only ice factory to retain the majority of its machinery in situ. In this sense, the building retains a significance that stretches far beyond the immediate area of the docks, but is also in itself an irreplaceable element in the dockland streetscape, reflecting the unique achievement of Grimsby’s fishing industry which, at its height, required such a striking industrial intervention in order that the vast quantities of fish passing through the port could be kept fresh.

Materials, form and style

Many of the buildings within the dock area are relatively consistent in their use of materials, and the texture is largely typical of a late 19th-century and early 20th-century industrial area in the north of England, with red-brick structures relieved by stone or brick lintels and under Welsh slate roofs. There is some degree of variety within this overall pattern, with a number of buildings using polychrome brickwork and a limited amount of render (though the majority of this is a modern accretion), but it was not until the 1930s and beyond, with buildings using more modern materials such as concrete and corrugated metal in their construction, that an identifiably new texture was introduced to the built environment of the area.

Certain of the buildings display a highly distinctive form, such as the massive bulk of the Grimsby Ice Factory, and the smokehouse portions of the fish processing works that, by means of towers, louvred ridge vents and cowls, are strikingly differentiated and contribute powerfully to the special character of the area. Buildings that contained at least some space for warehousing are also usually identifiable by having gable-end frontages, a practical response to the narrow and deep building plots. Many of these buildings are not dissimilar to the sort of commercial premises found along a typical late 19th-century ribbon development in the heart of an urban residential area, or in an industrial or workshop district. The general principle that underpins the multitude of forms that are found here, however, is that they are all bound tightly together by a community of economic interests and by a dense web of highly specific commercial connections. There is no building here that does not owe its existence to the complex requirements of the maritime and fishing industries, nor any building that sets out deliberately to delight the eye except where commercial pride and expediency demand it.

A degree of uniformity can be detected amongst all of the building types within the area, most particularly in their stylistic treatment. The majority of the buildings are plainly functional in style, only displaying design flair in highly distinctive but ultimately utilitarian features such as smoke cowls. There are, however, a significant number of buildings that, for the purposes of commercial promotion – especially in retail premises on or immediately around Fish Dock Road – display the typically eclectic range of stylistic features found from the mid-19th-century to the mid-20th-century, although focussed very much on the middle of that period. This includes examples of Italianate decoration from buildings dating to the earliest origins of the docks in the 1850s, to touches of, for example, neo-Gothic, Tudor, Dutch and Romanesque styles as the area was gradually developed. In this, as in every other aspect of the appearance and form of buildings, there is an overall sense of a complex pattern of individual endeavours within a broader plan dictated only by the concerns of space and function.

Integrity of survival

The streetscape of the dock area has survived to a considerable degree, and although there have been various instances of buildings being redeveloped on the same site, this has been part of a process of gradual renewal which has seen the evolving community of fishing industry businesses and their changing needs reflected in the changing building stock. Typically the newer buildings have not departed radically from the scale and massing of those they have replaced. There are a number of small empty sites within the area resulting from demolition, most notably in the south-west of the area around the Grimsby Ice Factory and in the centre of the triangular block bounded by Surtees Street, Henderson Street and Cross Street, where some minor streets and courts have been replaced with open space. These are notable exceptions to the general trend of a high degree of survival.

Within the estate of buildings on the dock peninsula, the present condition of the surviving historic fabric itself is generally good, with many of the structures having been maintained in continuous – if gradually evolving – use since their date of construction. There have, of course, been superficial and cosmetic changes to many of the buildings that reflect changing commercial needs, but this detracts little from the overwhelmingly intact historic scale and texture of the streets and buildings within the dock area.

One of the main legacies of Grimsby’s achievement in creating the world’s busiest fishing port by the late 19th-century is that this area of the town contains the greatest concentration of fish-processing buildings known in England. Hull provides the closest regional comparison, as Grimsby’s only serious rival in the trade, but here numbers of fish-processing buildings are smaller and the surviving examples are more scattered (13).

Other significant east coast fishing ports of the same period (for example Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft) are a good deal smaller than Grimsby and the remains of the buildings of the industry in them typically represent an earlier, less industrial phase in the development of the fish trade. On the south coast of England, the group of net and tackle stores on the beach at Hastings offers a striking example of grouped fishing-related structures, but again of a very different type and age (14). More particularly, these examples lack the sheer range and concentration of closely related activities (undiluted by general civic functions) seen within Grimsby’s densely built-up fish dock area, which confers on it such a rare, distinctive and appealing character.

Conclusion

The peninsula of man-made land situated between Grimsby’s fish dock complex and the Royal Dock constitutes a nationally significant example of an area continuously dominated by the fishing industry for more than 150 years. The collection of buildings in this area is of considerable historic worth, and reflects a wide range of activities associated with fishing and fish-processing, from landing the fresh catch at the quayside to the dispatch of processed products to markets across the country, especially by rail.

Several of the building types occurring within the fish dock area are unique to centres of fish processing, such as the smokehouses with their louvred ridge vents and cowls, and help to confer a special character on the area. Grimsby docks contains the largest surviving group of such fish-processing buildings and overall includes the largest single concentration of fishing-related historic buildings in England. The buildings erected along the streets and quaysides of the dock area from the 1850s onwards have shown a remarkable capacity for survival, evolving gradually over time to meet new commercial needs, but in general preserving the densely built-up historic fabric of the area in continuing fishing-related uses.

The area is distinguished further by its physical isolation from Grimsby’s town centre, having been developed on land reclaimed from the River Humber some distance from the historic core of the town. This land was used to engineer a thoroughly advanced complex of docks, fully integrated with the railway system and conducive to intensive, highly efficient forms of industry and movement. The specialised use of the dock peninsula has created a complete and self-contained historic environment, with highly distinctive characteristics. The majority of the buildings in the area are associated with the fishing industry, directly or indirectly, and are densely concentrated in the limited space available amongst railways, roads and quaysides. Grimsby’s fishing industry is remarkable historically for the speed of its growth and for its wholesale adoption of the latest technology; its legacy is the remarkable set of buildings that were developed over time to exploit the numerous opportunities that the booming port afforded. These buildings are an important reminder of the most 14 buoyant period of the town’s growth, from the middle of the 19th century to the early decades of the 20th, and represent an irreplaceable resource for understanding the nature of this growth and the special character of the processing businesses and ancillary trades that developed to serve the fishing industry.

Notes

1 Nikolaus Pevsner, John Harris and Nicholas Antram The Buildings of England: Lincolnshire (Penguin Books, 2nd ed, 1989), 337 & Edward Gillett, A History of Grimsby, University of Hull Press (1992),31-47

2 Gillett, 1992, 231

3 George Dow, Great Central, Volume I, Locomotive Publishing Co. (1959), 85

4 Gillett, 1992, 223

5 Alan Dowling, Grimsby: making the town 1800-1914, Phillimore and Co. (2007), 50

6 Gillett 1992, 231

7 Gillett, 1992, 231

8 Dowling, 2007, 49

9 Gordon Jackson The History and Archaeology of Ports (World’s Work 1983), 90

10 Jackson, 1983, 92

11 Jackson, 1983, 90

12 Sather and Associates, Rapid Survey of Fish Smoking Houses and Associated Buildings in Hull and Grimsby, prepared for English Heritage, June 2002

13 Sather and Associates, 2002

14 In the case of Hastings, it should be noted that all the buildings relevant to the fishing trade are listed and also fall within a Conservation Area; the listing description notes that the structures ‘form a very important feature of the Old Town of Hastings’.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Map showing part of Grimsby Docks. The report area is marked approximately by the heavy black line 16

Appendix 2: Report area in 1890, First Edition OS Map 17

Appendix 3: Goad Insurance Plan for Grimsby Docks, 1896 base layer with additions up to 1949 18

Appendix 4: Aerial photograph showing the report area in June 1992 © English Heritage/NMR 19

Appendix 5: Photographs of the report area, taken February 2009

Keith Graham Fish Curers/Smokers, Cross Street

Surtees Street showing a variety of buildings including, with the tower and cowl, MTL Fisheries (fish processing) 20 .

Russell Grant Ltd, former butcher shop and warehousing, part of Cosalt estate of buildings, at corner of Fish Dock Road, Hutton Street and Cross Street 21

Appendix 6: Photograph of Fish Dock Road c. 1900 showing the Cosalt building on the left (Source: P. Chapman) 22

Recent Comments